Body Politic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The body politic is a polity—such as a

The body politic is a polity—such as a

The development of the doctrine of the king's two bodies can be traced in the ''Reports'' of

The development of the doctrine of the king's two bodies can be traced in the ''Reports'' of

Aside from the doctrine of the king's two bodies, the conventional image of the whole of the realm as a body politic had also remained in use in Stuart England:

Aside from the doctrine of the king's two bodies, the conventional image of the whole of the realm as a body politic had also remained in use in Stuart England:

The body politic is a polity—such as a

The body politic is a polity—such as a city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

, realm, or state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

—considered metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide (or obscure) clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are often compared wi ...

ically as a physical body. Historically, the sovereign is typically portrayed as the body's head, and the analogy may also be extended to other anatomical parts, as in political readings of Aesop

Aesop ( or ; , ; c. 620–564 BCE) was a Greek fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as ''Aesop's Fables''. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales c ...

's fable of "The Belly and the Members

The Belly and the Members is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 130 in the Perry Index. It has been interpreted in varying political contexts over the centuries.

The Fable

There are several versions of the fable. In early Greek sources it co ...

". The image originates in ancient Greek philosophy, beginning in the 6th century BC, and was later extended in Roman philosophy. Following the high and late medieval

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

revival of the Byzantine ''Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

'' in Latin Europe, the "body politic" took on a jurisprudential significance by being identified with the legal theory of the corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and ...

, gaining salience in political thought from the 13th century on. In English law the image of the body politic developed into the theory of the king's two bodies and the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

as corporation sole

A corporation sole is a legal entity consisting of a single ("sole") incorporated office, occupied by a single ("sole") natural person.

.

The metaphor was elaborated further from the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

on, as medical knowledge based on Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

was challenged by thinkers such as William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions in anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, the systemic circulation and propert ...

. Analogies were drawn between supposed causes of disease and disorder and their equivalents in the political field, viewed as plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

s or infections that might be remedied with purges

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another organization, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertak ...

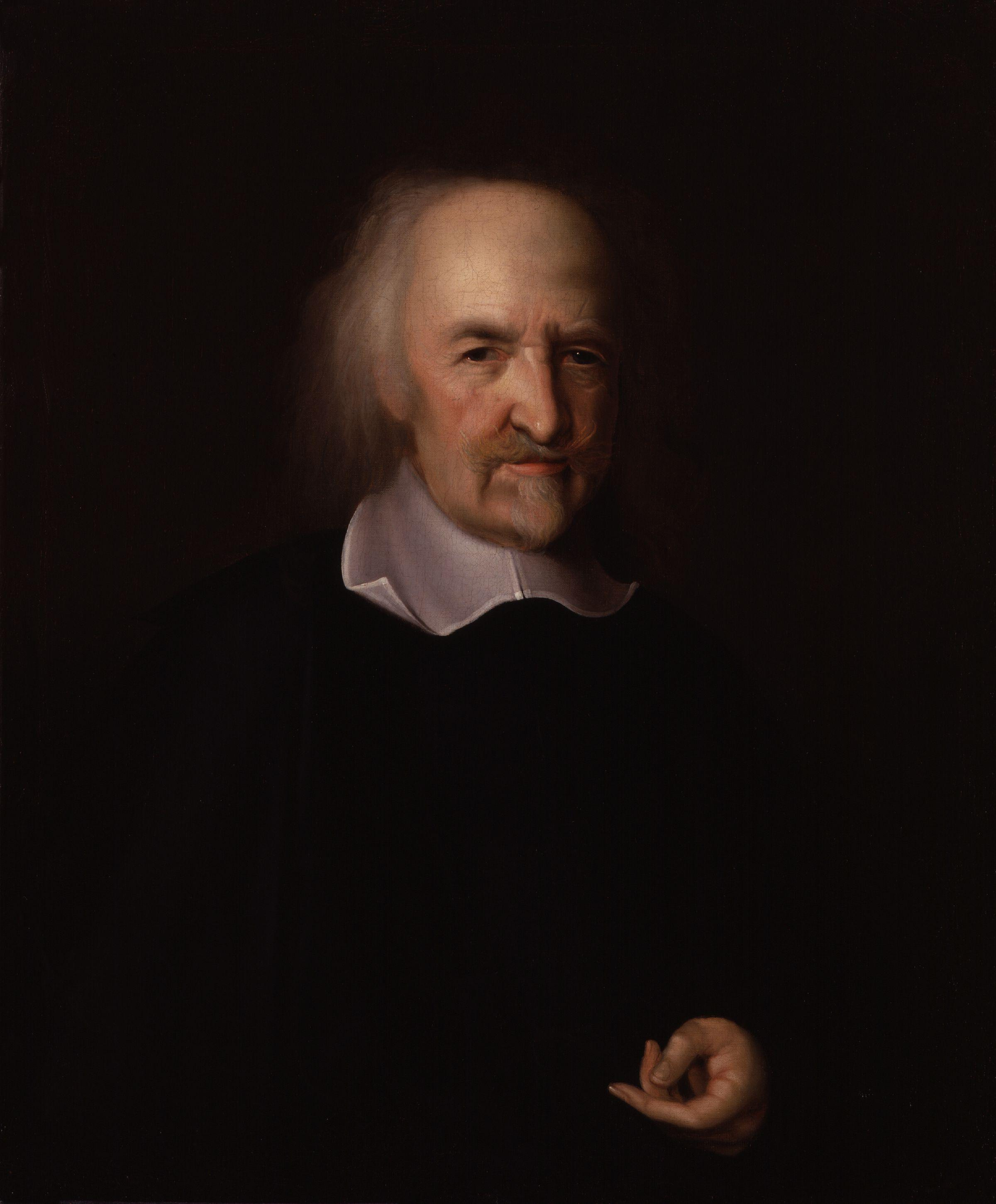

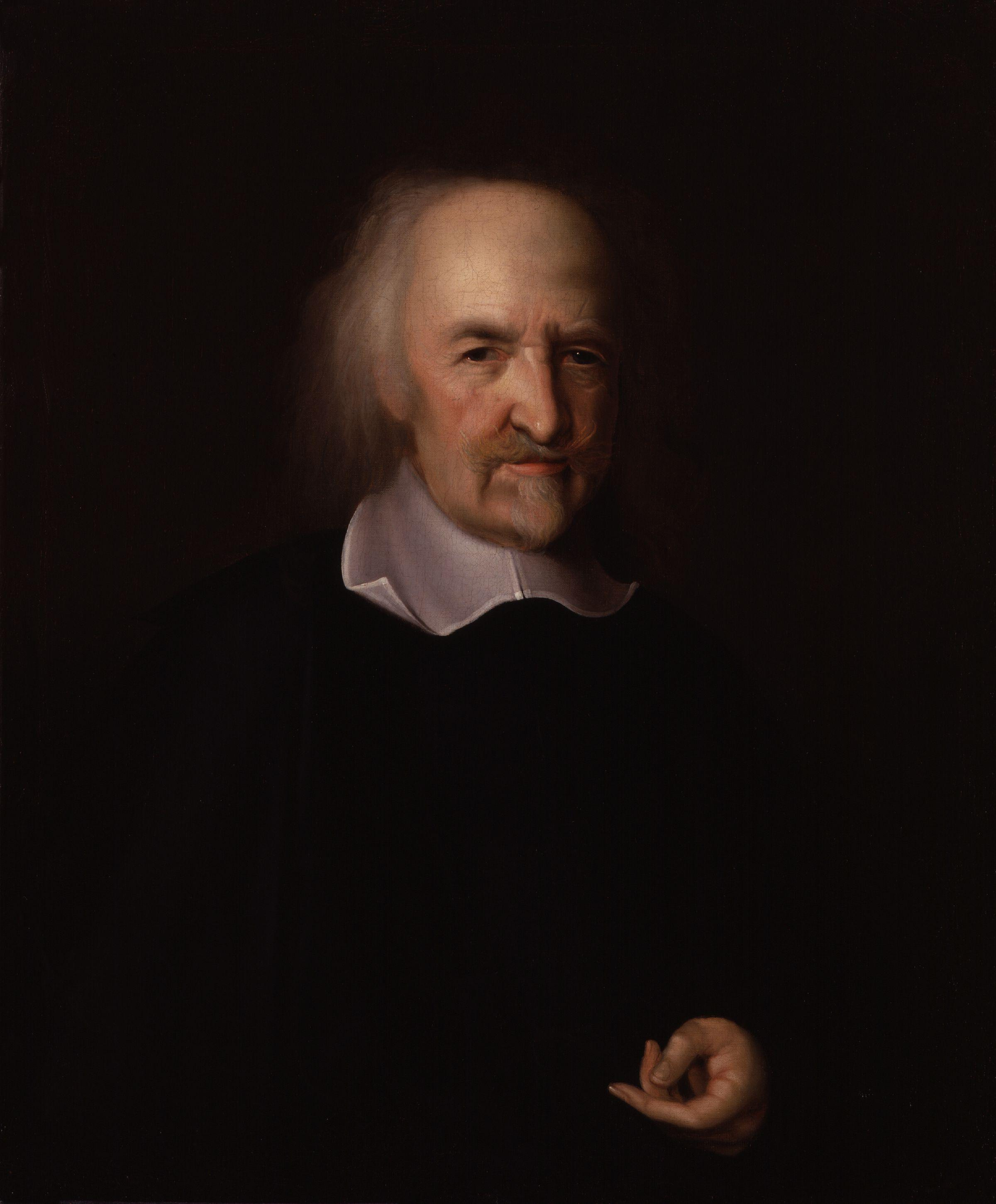

and nostrums. The 17th century writings of Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

developed the image of the body politic into a modern theory of the state as an artificial person. Parallel terms deriving from the Latin exist in other European languages.

Etymology

The term ''body politic'' derives fromMedieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functione ...

''corpus politicum'', which itself developed from ''corpus mysticum'', originally designating the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

as the mystical body of Christ

In Christian theology, the term Body of Christ () has two main but separate meanings: it may refer to Jesus' words over the bread at the celebration of the Jewish feast of Passover that "This is my body" in (see Last Supper), or it may refer to ...

but extended to politics from the 11th century on in the form ''corpus reipublicae'' (''mysticum''), "(mystical) body of the commonwealth". Parallel terms exist in other European languages, such as Italian ''corpo politico'', Polish ''ciało polityczne'', and German ''Staatskörper'' ("state body"). An equivalent early modern French term is ''corps-état''; contemporary French uses ''corps politique''.

History

Classical philosophy

The Western concept of the "body politic", originally meaning a humansociety

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

considered as a collective body, originated in classical Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Roman philosophy. The general metaphor emerged in the 6th century BC, with the Athenian statesman Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

and the poet Theognis

Theognis of Megara ( grc-gre, Θέογνις ὁ Μεγαρεύς, ''Théognis ho Megareús'') was a Greek lyric poet active in approximately the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, f ...

describing cities (''poleis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

'') in biological terms as "pregnant" or "wounded". Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's '' Republic'' provided one of its most influential formulations. The term itself, however—in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

, grc, τῆς πόλεως σῶμα, tēs poleōs sōma, label=none, "the body of the state"—appears as such for the first time in the late 4th century Athenian orators Dinarch Dinarchus or Dinarch ( el, Δείναρχος; Corinth, c. 361 – c. 291 BC) was a Logographer (legal), logographer (speechwriter) in Ancient Greece. He was the last of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aris ...

and Hypereides

Hypereides or Hyperides ( grc-gre, Ὑπερείδης, ''Hypereidēs''; c. 390 – 322 BC; English pronunciation with the stress variably on the penultimate or antepenultimate syllable) was an Athenian logographer (speech writer). He was one ...

at the beginning of the Hellenistic era

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

. In these early formulations, the anatomical detail of the body politic was relatively limited: Greek thinkers typically confined themselves to distinguishing the ruler as head of the body, and comparing political '' stasis'', that is, crises of the state, to biological disease.

The image of the body politic occupied a central place in the political thought of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

, and the Romans were the first to develop the anatomy of the "body" in full detail, endowing it with nerves, "blood, breath, limbs, and organs". In its origins, the concept was particularly connected to a politicised version of Aesop

Aesop ( or ; , ; c. 620–564 BCE) was a Greek fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as ''Aesop's Fables''. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales c ...

's fable of "The Belly and the Members

The Belly and the Members is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 130 in the Perry Index. It has been interpreted in varying political contexts over the centuries.

The Fable

There are several versions of the fable. In early Greek sources it co ...

", told in relation to the first ''secessio plebis'', the temporary departure of the plebeian order from Rome in 495–93 BC.. On the account of the Roman historian Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, a senator explained the situation to the plebeians by a metaphor: the various members of the Roman body had become angry that the "stomach", the patricians

The patricians (from la, patricius, Greek: πατρίκιος) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom, and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after ...

, consumed their labours while providing nothing in return. However, upon their secession, they became feeble and realised that the stomach's digestion had provided them vital energy. Convinced by this story, the plebeians returned to Rome, and the Roman body was made whole and functional. This legend formed a paradigm for "nearly all surviving republican discourse of the body politic".

Late republican orators developed the image further, comparing attacks on Roman institutions to mutilations of the republic's body. During the First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The constitution of the Roman republic had many ve ...

in 59 BC, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

described the Roman state as "dying of a new sort of disease". Lucan's ''Pharsalia

''De Bello Civili'' (; ''On the Civil War''), more commonly referred to as the ''Pharsalia'', is a Roman epic poem written by the poet Lucan, detailing the civil war between Julius Caesar and the forces of the Roman Senate led by Pompey the Gr ...

'', written in the early imperial era in the 60s AD, abounded in this kind of imagery. Depicting the dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in tim ...

Sulla as a surgeon out of control who had butchered the Roman body politic in the process of cutting out its putrefied limbs, Lucan used vivid organic language to portray the decline of the Roman Republic as a literal process of decay, its seas and rivers becoming choked with blood and gore.

Medieval usage

The metaphor of the body politic remained in use after thefall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

. The Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

Islamic philosopher al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Isl ...

, known in the West as Alpharabius, discussed the image in his work ''The Perfect State'' (c. 940), stating, "The excellent city resembles the perfect and healthy body, all of whose limbs cooperate to make the life of the animal perfect". John of Salisbury

John of Salisbury (late 1110s – 25 October 1180), who described himself as Johannes Parvus ("John the Little"), was an English author, philosopher, educationalist, diplomat and bishop of Chartres.

Early life and education

Born at Salisbury, E ...

gave it a definitive Latin high medieval form in his ''Policraticus

''Policraticus'' is a work by John of Salisbury, written around 1159. Sometimes called the first complete medieval work of political theory, it belongs, at least in part, to the genre of advice literature addressed to rulers known as " mirrors for ...

'' around 1159: the king was the body's head; the priest was the soul; the councillors were the heart; the eyes, ears, and tongue were the magistrates of the law; one hand, the army, held a weapon; the other, without a weapon, was the realm's justice. The body's feet were the common people. Each member of the body had its vocation

A vocation () is an occupation to which a person is especially drawn or for which they are suited, trained or qualified. People can be given information about a new occupation through student orientation. Though now often used in non-religious ...

, and each was beholden to work in harmony for the benefit of the whole body.

In the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

, the concept of the corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and ...

, a legal person

In law, a legal person is any person or 'thing' (less ambiguously, any legal entity) that can do the things a human person is usually able to do in law – such as enter into contracts, sue and be sued, own property, and so on. The reason for ...

made up of a group of real individuals, gave the idea of a body politic judicial significance. The corporation had emerged in imperial Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

under the name ''universitas'', and a formulation of the concept attributed to Ulpian

Ulpian (; la, Gnaeus Domitius Annius Ulpianus; c. 170223? 228?) was a Roman jurist born in Tyre. He was considered one of the great legal authorities of his time and was one of the five jurists upon whom decisions were to be based according to ...

was collected in the 6th century '' Digest'' of Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renova ...

during the early Byzantine era

The Byzantine calendar, also called the Roman calendar, the Creation Era of Constantinople or the Era of the World ( grc, Ἔτη Γενέσεως Κόσμου κατὰ Ῥωμαίους, also or , abbreviated as ε.Κ.; literal translation of ...

. The ''Digest'', along with the other parts of Justinian's ''Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

'', became the bedrock of medieval civil law upon its recovery and annotation by the glossator

The scholars of the 11th- and 12th-century legal schools in Italy, France and Germany are identified as glossators in a specific sense. They studied Roman law based on the '' Digesta'', the ''Codex'' of Justinian, the ''Authenticum'' (an abridged ...

s beginning in the 11th century. It remained for the glossators' 13th century successors, the commentators

Commentator or commentators may refer to:

* Commentator (historical) or Postglossator, a member of a European legal school that arose in France in the fourteenth century

* Commentator (horse) (foaled 2001), American Thoroughbred racehorse

* The Co ...

—especially Baldus de Ubaldis

Baldus de Ubaldis (Italian: ''Baldo degli Ubaldi''; 1327 – 28 April 1400) was an Italian jurist, and a leading figure in Medieval Roman Law and the school of Postglossators.

Life

A member of the noble family of the Ubaldi (Baldeschi), ...

—to develop the idea of the corporation as a ''persona ficta'', a fictive person, and apply the concept to human societies as a whole.

Where his jurist predecessor Bartolus of Saxoferrato conceived the corporation in essentially legal terms, Baldus expressly connected the corporation theory to the ancient, biological and political concept of the body politic. For Baldus, not only was man, in Aristotelian terms, a "political animal", but the whole ''populus'', the body of the people, formed a type of political animal in itself: a ''populus'' "has government as part of tsexistence, just as every animal is ruled by its own spirit and soul". Baldus equated the body politic with the '' respublica'', the state or realm, stating that it "cannot die, and for this reason it is said that it has no heir, because it always lives on in itself". From here, the image of the body politic became prominent in the medieval imagination. In Canto XVIII of his '' Paradiso'', for instance, Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian people, Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', origin ...

, writing in the early 14th century, presents the Roman Empire as a corporate body in the form of an imperial eagle, its body made of souls. The French court writer Christine de Pizan discussed the concept at length in her ''Book of the Body Politic'' (1407).

The idea of the body politic, rendered in legal terms through corporation theory, also drew natural comparison to the theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

concept of the church as a ''corpus mysticum'', the mystical body of Christ

In Christian theology, the term Body of Christ () has two main but separate meanings: it may refer to Jesus' words over the bread at the celebration of the Jewish feast of Passover that "This is my body" in (see Last Supper), or it may refer to ...

. The concept of the people as a ''corpus mysticum'' also featured in Baldus, and the idea that the realm of France was a ''corpus mysticum'' formed an important part of late medieval French jurisprudence. , around 1418–19, described the French laws of succession as established by the "whole civic or mystical body of the realm", and the Parlement of Paris

The Parliament of Paris (french: Parlement de Paris) was the oldest ''parlement'' in the Kingdom of France, formed in the 14th century. It was fixed in Paris by Philip IV of France in 1302. The Parliament of Paris would hold sessions inside the ...

in 1489 proclaimed itself a "mystical body" composed of both ecclesiastics and laymen, representing the "body of the king". From at least the 14th century, the doctrine developed that the French kings were mystically married to the body politic; at the coronation of Henry II in 1547, he was said to have "solemnly married his realm". The English jurist John Fortescue also invoked the "mystical body" in his ' (c. 1470): just as a physical body is "held together by the nerves", the mystical body of the realm is held together by the law, and

The king's body politic

In England

In Tudor andStuart England

Stuart may refer to:

Names

*Stuart (name), a given name and surname (and list of people with the name) Automobile

* Stuart (automobile)

Places

Australia Generally

*Stuart Highway, connecting South Australia and the Northern Territory

Northe ...

, the concept of the body politic was given a peculiar additional significance through the idea of the ''king's two bodies'', the doctrine discussed by the German-American medievalist Ernst Kantorowicz in his eponymous work. This legal doctrine held that the monarch had two bodies: the physical "king body natural" and the immortal "King body politic". Upon the "demise" of an individual king, his body natural fell away, but the body politic lived on.. This was an indigenous development of English law without a precise equivalent in the rest of Europe. Extending the identification of the body politic as a corporation, English jurists argued that the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

was a "corporation sole

A corporation sole is a legal entity consisting of a single ("sole") incorporated office, occupied by a single ("sole") natural person.

": a corporation made up of one body politic that was at the same time the body of the realm and its parliamentary estates, and also the body of the royal dignity itself—two concepts of the body politic that were conflated and fused.

The development of the doctrine of the king's two bodies can be traced in the ''Reports'' of

The development of the doctrine of the king's two bodies can be traced in the ''Reports'' of Edmund Plowden

Sir Edmund Plowden (1519/20 – 6 February 1585) was a distinguished English lawyer, legal scholar and theorist during the late Tudor period.

Early life

Plowden was born at Plowden Hall, Lydbury North, Shropshire. He was the son of Humphrey ...

. In the 1561 ''Case of the Duchy of Lancaster'', which concerned whether an earlier gift of land made by Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

could be voided on account of his "nonage", that is, his immaturity, the judges held that it could not: the king's "Body politic, which is annexed to his Body natural, takes away the Imbecility of his Body natural". The king's body politic, then, "that cannot be seen or handled", annexes the body natural and "wipes away" all its defects. What was more, the body politic rendered the king immortal as an individual: as the judges in the case ''Hill v. Grange'' argued in 1556, once the king had made an act, "he as King never dies, but the King, in which Name it has Relation to him, does ever continue"—thus, they held, Henry VIII was still "alive", a decade after his physical death.

The doctrine of the two bodies could serve to limit the powers of the real king. When Edward Coke, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

The chief justice of the Common Pleas was the head of the Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench or Common Place, which was the second-highest common law court in the English legal system until 1875, when it, along with the othe ...

at the time, reported the way in which judges had differentiated the bodies in 1608, he noted that it was the "natural body" of the king that was created by God—the "politic body", by contrast, was "framed by the policy of man". In the ''Case of Prohibitions'' of the same year, Coke denied the king "in his own person" any right to administer justice or order arrests. Finally, in its declaration of 27 May 1642 shortly before the start of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

drew on the theory to invoke the powers of the body politic of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

against his body natural, stating:

The 18th century jurist William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family ...

, in Book I of his '' Commentaries on the Laws of England'' (1765), summarised the doctrine of the king's body politic as it subsequently developed after the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

: the king "in his political capacity" manifests "absolute ''perfection''"; he can "do no wrong", nor even is he capable of "''thinking'' wrong"; he can have no defect, and is never in law "a minor or under age". Indeed, Blackstone says, if an heir to the throne should accede while "attainted of treason or felony", his assumption of the crown "would purge the attainder ''ipso facto''". The king manifests "absolute immortality": "Henry, Edward, or George may die; but the king survives them all". Soon after the appearance of the ''Commentaries'', however, Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

mounted an extensive attack on Blackstone which the historian Quentin Skinner describes as "almost lethal" to the theory: legal fictions like the body politic, Bentham argued, were conducive to royal absolutism and should be entirely avoided in law. Bentham's position dominated later British legal thinking, and though aspects of the theory of the body politic would survive in subsequent jurisprudence, the idea of the Crown as a corporation sole was widely critiqued.

In the late 19th century, Frederic William Maitland

Frederic William Maitland (28 May 1850 – ) was an English historian and lawyer who is regarded as the modern father of English legal history.

Early life and education, 1850–72

Frederic William Maitland was born at 53 Guilford Street, L ...

revived the legal discourse of the king's two bodies, arguing that the concept of the Crown as corporation sole had originated from the amalgamation of medieval civil law with the law of church property. He proposed, in contrast, to view the Crown as an ordinary corporation aggregate, that is, a corporation of many people, with a view to describing the legal personhood of the state.

In France

A related but contrasting concept in France was the doctrine termed by Sarah Hanley the king's ''one'' body, summarised byJean Bodin

Jean Bodin (; c. 1530 – 1596) was a French jurist and political philosopher, member of the Parlement of Paris and professor of law in Toulouse. He is known for his theory of sovereignty. He was also an influential writer on demonology.

Bodi ...

in his own 1576 pronouncement that "the king never dies". Rather than distinguishing the immortal body politic from the mortal body natural of the king, as in the English theory, the French doctrine conflated the two, arguing that the Salic law had established a single king body politic and natural that constantly regenerated through the biological reproduction of the royal line. The body politic, on this account, was biological and necessarily male, and 15th century French jurists such as Jean Juvénal des Ursins

Jean (II) Juvénal des Ursins (1388–1473), the son of the royal jurist and provost of the merchants of Paris Jean Juvénal, was a French cleric and historian. He is the author of several legal treatises and clerical publications and the ''Histoi ...

argued on this basis for the exclusion of female heirs to the crown—since, they argued, the king of France was a "virile office". In the ''ancien régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for ...

'', the king's heir was held to assimilate the body politic of the old king in a physical "transfer of corporeality" upon his accession.

In the United States

James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

in the second charter for Virginia, as well as both the Plymouth and Massachusetts Charter

The Massachusetts Charter of 1691 was a charter that formally established the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Issued by the government of William III and Mary II, the corulers of the Kingdom of England, the charter defined the government of the co ...

, grant body politic.

Hobbesian state theory

Aside from the doctrine of the king's two bodies, the conventional image of the whole of the realm as a body politic had also remained in use in Stuart England:

Aside from the doctrine of the king's two bodies, the conventional image of the whole of the realm as a body politic had also remained in use in Stuart England: James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

compared the office of the king to "the office of the head towards the body". Upon the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, however, parliamentarians such as William Bridge

William Bridge (c. 1600 – 1670) was a leading English Independent minister, preacher, and religious and political writer.

Life

A native of Cambridgeshire, the Rev. William Bridge was probably born in or around the year 1600. He studied at Em ...

put forward the argument that the "ruling power" belonged originally to "the whole people or body politicke", who could revoke it from the monarch. The execution of Charles I

The execution of Charles I by beheading occurred on Tuesday, 30 January 1649 outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall. The execution was the culmination of political and military conflicts between the royalists and the parliamentarians in E ...

in 1649 made necessary a radical revision of the whole concept. In 1651, Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

's ''Leviathan

Leviathan (; he, לִוְיָתָן, ) is a sea serpent noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, the Book of Amos, and, according to some ...

'' made a decisive contribution to this effect, reviving the concept while endowing it with new features. Against the parliamentarians, Hobbes maintained that sovereignty was absolute and the head could certainly not be "of lesse power" than the body of the people; against the royal absolutists, however, he developed the idea of a social contract, emphasising that the body politic—Leviathan, the "mortal god"—was fictional and artificial rather than natural, derived from an original decision by the people to constitute a sovereign.

Hobbes's theory of the body politic exercised an important influence on subsequent political thinkers, who both repeated and modified it. Republican partisans of the Commonwealth presented alternative figurations of the metaphor in defence of the parliamentarian model. James Harrington, in his 1656 '' Commonwealth of Oceana'', argued that "the delivery of a Model Government ... is no less than political Anatomy"; it must "imbrace all those Muscles, Nerves, Arterys and Bones, which are necessary to any Function of a well order'd Commonwealth". Invoking William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions in anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, the systemic circulation and propert ...

's recent discovery of the circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

, Harrington presented the body politic as a dynamic system of political circulation, comparing his ideal bicameral legislature, for example, to the ventricles of the human heart. In contrast to Hobbes, the "head" was once more dependent on the people: the execution of the law must follow the law itself, so that "''Leviathan'' may see, that the hand or sword that executeth the Law is ''in'' it, and ''not above'' it". In Germany, Samuel von Pufendorf recapitulated Hobbes's explanation of the origin of the state as a social contract, but extended his notion of personhood to argue that the state must be a specifically moral person with a rational nature, and not simply coercive power.

In the 18th century, Hobbes's theory of the state as an artificial body politic gained wide acceptance both in Britain and continental Europe. Thomas Pownall

Thomas Pownall (bapt. 4 September 1722 N.S. – 25 February 1805) was a British colonial official and politician. He was governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay from 1757 to 1760, and afterwards sat in the House of Commons from 1767 t ...

, later the British governor of Massachusetts and a proponent of American liberty, drew on Hobbes's theory in his 1752 ''Principles of Polity'' to argue that "the whole Body politic" should be conceived as "one Person"; states were "distinct ''Persons'' and independent". At around the same time, the Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel

Emer (Emmerich) de Vattel ( 25 April 171428 December 1767) was an international lawyer. He was born in Couvet in the Principality of Neuchâtel (now a canton part of Switzerland but part of Prussia at the time) in 1714 and died in 1767. He was l ...

pronounced that "states are bodies politic", "moral persons" with their own "understanding and ... will", a statement that would become accepted international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

.

The tension between organic understandings of the body politic and theories emphasizing its artificial character formed a theme in English political debates in this period. Writing in 1780, during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, the British reformist John Cartwright emphasised the artificial and immortal character of the body politic in order to refute the use of biological analogies in conservative rhetoric. Arguing that it was better conceived as a machine operating by the "due action and re-action of the ... springs of the constitution" than a human body, he termed "the ''body'' politic" a "careless figurative expression": "It is not corporeal ... not formed from the dust of the earth. It is purely intellectual; and its life-spring is truth."

Modern law

The English term "body politic" is sometimes used in modern legal contexts to describe a type oflegal person

In law, a legal person is any person or 'thing' (less ambiguously, any legal entity) that can do the things a human person is usually able to do in law – such as enter into contracts, sue and be sued, own property, and so on. The reason for ...

, typically the state itself or an entity connected to it. A body politic is a type of taxable legal person in British law

The United Kingdom has four legal systems, each of which derives from a particular geographical area for a variety of historical reasons: English and Welsh law, Scots law, Northern Ireland law, and, since 2007, purely Welsh law (as a result of ...

, for example, and likewise a class of legal person in Indian law

The legal system of India consists of civil, common law and customary, Islamic ethics, or religious law within the legal framework inherited from the colonial era and various legislation first introduced by the British are still in effect i ...

. In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, a municipal corporation

A municipal corporation is the legal term for a local governing body, including (but not necessarily limited to) cities, counties, towns, townships, charter townships, villages, and boroughs. The term can also be used to describe municipally ...

is considered a body politic, as opposed to a private body corporate. The U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

affirmed the theory of the state as an artificial body politic in the 1851 case ''Cotton v. United States'', declaring that "every sovereign State is of necessity a body politic, or artificial person, and as such capable of making contracts and holding property, both real and personal", and differentiated the United States' powers as a sovereign from its rights as a body politic..

See also

*Social organism

Social organism is a sociological concept, or model, wherein a society or social structure is regarded as a "living organism". The various entities comprising a society, such as law, family, crime, etc., are examined as they interact with other e ...

, the concept in sociology

*'' Volkskörper'', the German "national body"

*'' Lex animata'', the king as the "living law"

*''Kokutai

is a concept in the Japanese language translatable as " system of government", "sovereignty", "national identity, essence and character", "national polity; body politic; national entity; basis for the Emperor's sovereignty; Japanese constitu ...

'', a related Japanese concept

* Royal ''we''

References

{{Reflist Political philosophy Biopolitics English legal terminology Political metaphors